Games for Cities

#3Citizen City/ Eindhoven

Partners:

You are a resident of Woensel-Noord, Eindhoven’s largest working-class neighbourhood. You don’t use a smartphone and neither you nor your partner make frequent use of the internet. And why would you, when all of your social and work-related contacts take place just around your home?

However, there is a problem. The City of Eindhoven is increasingly working towards becoming the ‘smartest city’ in the Netherlands, at the forefront of collecting and using big data in city-making strategies. Your city is using this data to inform and – as city officials keep promising – significantly improve the region’s future. This is all good and well; except that you are not connected to the virtual networks used to collect all of this data. So you will likely not be included in any of these databases.

How will these future solutions affect you, a long-time citizen of Eindhoven, when your daily life and experiences are not picked up by the ‘smart city’ monitors busy collecting endless amounts of clicks and GPS-locations? Will your concerns and needs be represented – let alone addressed – in this new form of citymaking? This situation drove us to formulate the Citizen City Challenge. With you and your communities’ interests in mind, we ask:

HOW CAN GAMES VOICE CITIZENS’ EVERYDAY STORIES AND EXPERIENCES IN THE TIME OF BIG DATA?

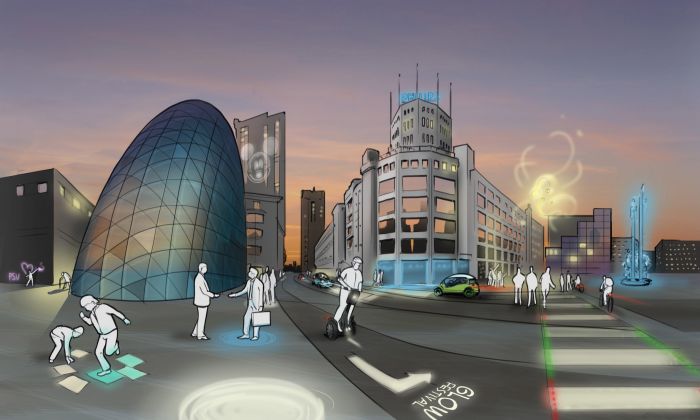

As an inherently interactive method, gaming has the ability to position itself right in the gap between technology and user. Moreover, it is a method that is able to both process the large amounts of information typical of smart-city innovations as well as present this in a user-friendly and intuitive format.

Het Nieuwe Instituut’s DATAstudio has been focussing on how citizens relate to digital data that is collected and used for policymaking by local governments. DATAStudio – a programme within the State of Eindhoven, and our local partners – have been conducting research into available data and technological capabilities combined with the reality of the street and the needs of residents. They are interested in what it means to residents to live in a ‘smart city’, and in promoting civic technologies. DATAstudio has been documenting in-depth stories of local residents through various workshops in Woensel-Noord. These rich individual stories can be found here, but they also illustrate the various ‘Data Deserts’ present in Eindhoven, leading to a range of proposals for tackling this issue. Based on this, Games for Cities was asked to develop a game to simultaneously improve the quality of data collected and empower citizens through making meaning out of data and helping them to take action. The City of Eindhoven and Design Academy Eindhoven, together with the Games for Cities team, engaged in prototyping three city-games for collecting more holistic and inclusive datasets, and simultaneously functioning as a platform for enhanced social connectedness.

Eindhoven’s challenge concerns TACKLING LONELINESS AND INCLUSION AMONG OLDER RESIDENTS who often fall through the net of smart city monitors.

This is particularly pressing for neighbourhoods such as Woensel-Noord, where one in five residents in the neighbourhood is above 65 years old. This neighbourhood is host to the highest proportion of elderly residents in Eindhoven, but it represents a trend in demographic distributions that will become increasingly more prevalent in the coming decades.

Eindhoven’s Citizen City Challenge was tackled through the following events:

Event #1

The Citizen City Game Talk Show

The Citizen City-Game Talk Show hosted a number of local and international experts discussing the role of gaming in creating more democratic cities in the time of big data.

The Talk Show provided a foundation and springboard for creativity during the Game Jam process that followed it. The Talk Show and Game Jam events took place at DesignHuis Eindhoven, with an expert on gerontology stimulating discussion around the need for developing quality social contacts. Following this, there as a roundtable discussion with various Eindhoven and urban design experts. Designers then received their design briefing from Linda Vlassenrood, city officials, housing corporations and the Seniors Platform in Woensel Noord.

Event #2

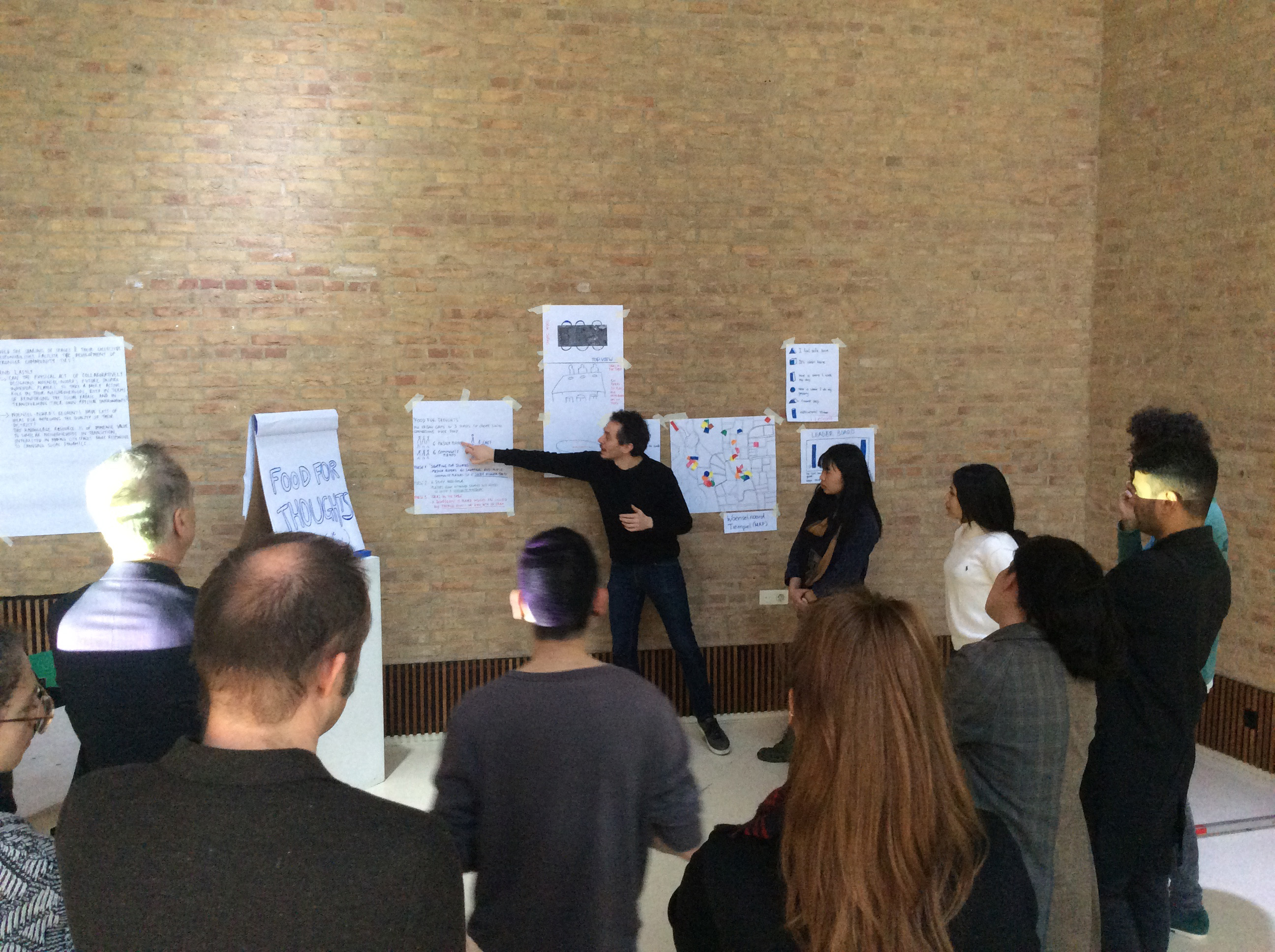

The Citizen City Game Jam

The Citizen City Game Jam brought together a team of designers, researchers, and design students who worked together with local residents to create three prototypes for co-creating citizen spaces. This took place over an intense 48-hour workshopping process on March 22nd and 23rd 2017, where 3 different but connected game prototypes were developed. The challenge now, is to knit the successful elements of each game together into one coherent game that can facilitate the development of quality relationships in Woensel-Noord. The primary result of this process will be a City-Game designed specifically for the elderly in Woensel-Noord. The three prototypes developed can be read about below:

The 3 game prototypes are:

1. Voedsel voor je Gedachten

2. de Tienduizend

3. Woensel Straks

Prototype 1: Voedsel voor je Gedachten

Food for Thoughts is a game to facilitate encounters and dialogue across generations through food, cooking, and recipes. People from the Tempel neighbourhood are invited for an improvised dinner party, where they are engaged in a conversation about urban issues over shared food and drinks. The game involves a team of organisers, 6 ‘master-players’ (highly motivated participants recruited before the game), 1 volunteer chef, 1 invited expert (on a specific topic such as the liveability of the neighbourhood for ageing adults), 6 ‘community-players’ (recruited by the master-players), and observers and researchers.

The game is divided in 3 phases. During phase 1, organisers, master-players, the expert and the chef meet together at the community centre. The expert introduces the theme of the day, while the chef introduces the menu of the day. Master-players then receive a list of groceries to buy, as well as money, and a mission to recruit 6 community-players. Master-players then go to the supermarket, buy groceries, and strike up conversations with fellow community-members. They ask for stories of neighbourhood experiences and cultural differences, and invite participants to join them for a dinner party – heading back to the community centre together. During phase 2, the chef and some players cook, and each player is asked to share a recipe that is somewhat related to one of the stories that was told, and that is somehow related to the neighbourhood. All stories and recipes shared are collected in a book, to be published at a later stage. Recipes learnt may also be ‘played’ in further game sessions. During phase 3, the table is set, and the tablecloth becomes the game-board. Each player receives food in a special plate with a different statement printed on it, (such as: “I feel safe here…”). Each player receives their game-pieces (4 pieces for each question), and the expert invites player 1 to read the statement on his plate to the rest of the table. Timed with an hourglass, players place their 4 game-pieces on places on the map that answer to question 1, and discussion ensues under the expert’s guidance. Once the hourglass ends discussion ends, and this process is repeated for questions 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6. Dessert is served and players propose concrete actions to the expert to address each of the mapped issues. Game-pieces are then tallied up for each location, and a leaderboard is generated indicating which locations receive more ‘votes’ for each question). This leaderboard is updated after each game session, representing a running total for where public sentiments are spatially situated.

Prototype 2: de Tienduizend

This is an Alternate Reality game where a wall has been placed around Woensel-Noord overnight, and the community is now cut off from any transactions that go beyond the wall. The entire game lasts 6 months (real-time), with each month representing a year in the game, and signalling the arrival of a new challenge. Residents receive news pamphlets in the post at the start of each month inviting them to participate in devising strategies for tackling (fictitious) events happening in their neighbourhood, which need to be overcome by community-led actions and resources. In reality, this has the potential for generating integrated communities that are engaged in spatial planning concerns. These events include, ‘an extreme weather event has led to flooding – how do we deal with this?’, or ‘the first child is born since the wall went up – how do we celebrate this?’ Do residents have any knowledge/skills on how to deal with such a disruption, or would they like to learn? Players then play with the current resources (human and otherwise) available to them within their neighbourhood, and in the process, they learn about their neighbours and how to create better living conditions together, producing collective knowledge. In each further episode, a report is included detailing previous solutions devised and the resident contributions made. A table is included where residents can fill in their skills, interests and resources that are situated in their neighbourhood. This offers an opportunity for residents to learn about their neighbours and what skills or interests they have, triggering the development of quality relationships, where relationships and collaborations have the potential of transcending the game environment. Player roles refer to the ‘pillars of society’, based either on what they have to offer or on what they’re interested in. Arriving players then choose which role they would like to assume in the game. Interventions and solutions centre around managing/mitigating the impacts of each new ‘shock’. The game works towards a ‘closing moment’ 6-months later, at which point there is a party and presentation where the new society built by residents is demonstrated and all the products of their interventions are present.

This game has multiple layers to it and is intended for players of all ages. Older adults are granted opportunities for increased visibility and action in their neighbourhood, facilitating decreased perceptions of social and spatial isolation. As players contribute towards the production of a collective intelligence and creativity regarding the necessary spatial interventions for improving the living conditions in their neighbourhood, spatial decision-makers become better informed and prepared for intervening.

Prototype 3: Woensel Straks

This game is based on research conducted by DATAstudio and their tentative suggestion for ‘Roomsel-Noord’. Briefly, Roomsel-Noord suggests that older adults may be interested in modifying their homes in order to accommodate flexible and temporal rental arrangements, where separating the ground floor from the top, or joining courtyard spaces with neighbours could increase the productivity of these spaces while also generating more socially connected and integrated communities. In playing for spatial and social connectedness, could different housing typologies facilitate more connected residents? The game is intended to offer a prototyping environment for testing these ideas with community members, and takes place over the course of 16 game sessions, each taking place in the living rooms of apartments in different parts of the neighbourhood. This will provide the game with immediate physical differences in the apartments and public environments within which the game is played, informing the challenges and discussions that take place in each game.

Woensel-Noord is identified in this game as a pioneering district with the knowledge and skills for thinking about how to respond to shifting age demographics. At the start of the game, players are able to choose which challenge they’d like to explore, and they must find 3 other players that are interested in tackling that challenge with them. Each challenge in the game relates to one of the four scales of play, and player groups then receive their ‘tools’ (models, maps and props) for facilitating their spatial engagement. The game thus makes jumping between spatial scales easier and more tangible for residents to engage with. The first scale of play is 1:1, which is the physical apartment that the game takes place in, and players playing challenges set at this scale are charged with re-imagining this physical space, with props such as red tape or fabric used to indicate spaces/walls in the apartment requiring alterations. The street scale is represented by a physical model of the entire street and is very modular and flexible, so that players can easily change the layout of the street, porches and apartments. Balconies and porches can be joined or pushed back, attic spaces can be added or removed, increasing the diversity of housing typologies and functions offered in the neighbourhood. Neighbourhood scale engagement is facilitated by a map and props that make it easier to relate to spatial reconfigurations at this scale. This might deal with challenges such as re-imagining local park spaces or other spaces for socialising in. The district scale has its own map and props and deals with issues such as re-imagining a district transport system. An expert is on hand during each game to guide player discussions and actions at each scale.

After each group has collaborated on proposals for tackling their challenge, one representative from each group pitches these ideas to other players in the room who vote either in agreement or disagreement. Following voting, feedback is given by other players in the room, giving the game-master further indication of the kinds of renovations and spatial reconfigurations that community members would be happy with. Pitches that receive the most votes of confidence from colleagues will have their models 3D printed (to collect at the next game session), as a trophy rewarding their input. These are also posted to a digital database of community solutions, accumulating as game sessions continue. Thus, player contributions do not evaporate, and feedback sessions are key to achieving genuine inclusiveness and empowerment.